Information architecture can be hard to explain. Sometimes it’s easier to learn by doing. The next time someone asks you what an information architect does, instead of stumbling through a confusing, multi-part definition, challenge them to a game!

The following four games will get you thinking like an information architect. To emerge as the winner, you’ll need to hone your skills at what Richard Saul Wurman might call “the creative organization of information”: producing words that relate to other words, intuiting the connections between different concepts, and uncovering meaning by structuring information in new ways.

Make sense? No? Well, try these games anyway. Not only are they fun in their own right, but they can be a helpful, hands-on guide for understanding what it is we do.

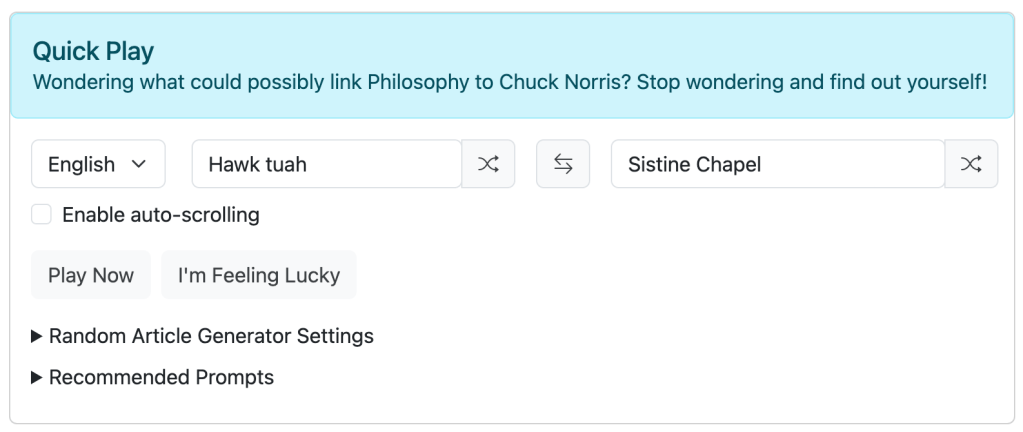

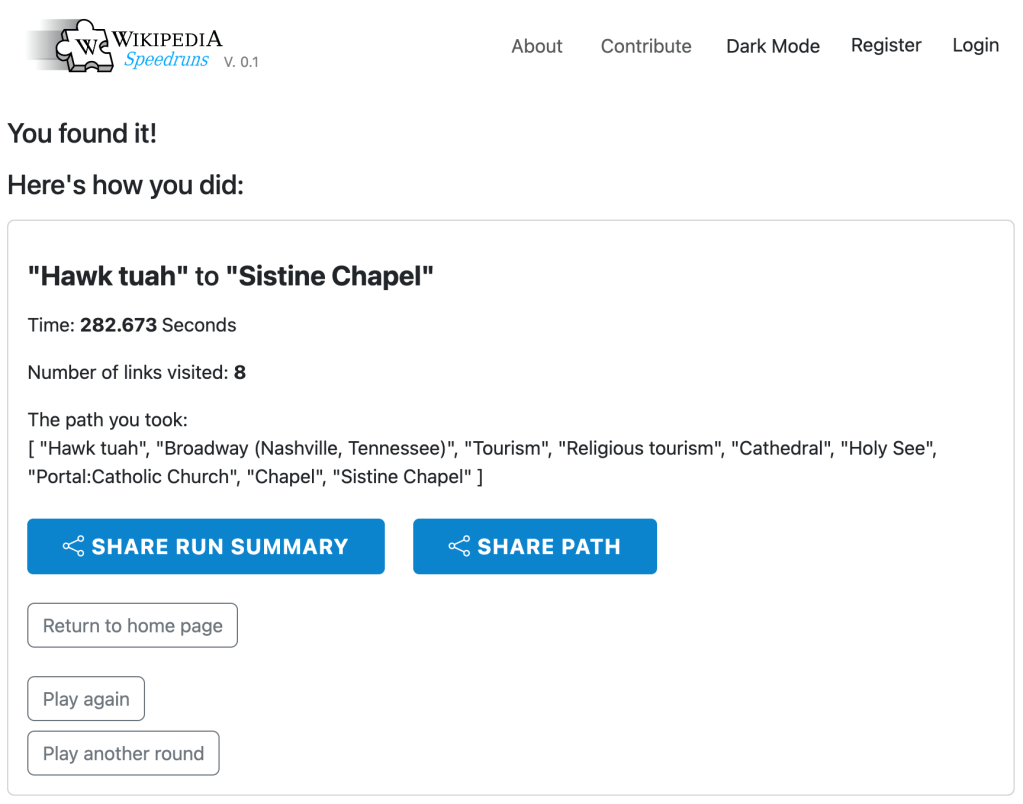

Wikipedia Speedruns

A “Wikipedia Speedrun” is a challenge to navigate from one particular Wikipedia article to another, as fast as possible, using only on-page links. Runs can be scored either by the fewest links clicked or the quickest time to reach the end.

Wikipedia Speedruns are made all the more challenging and fun when your start and end points are completely unrelated.

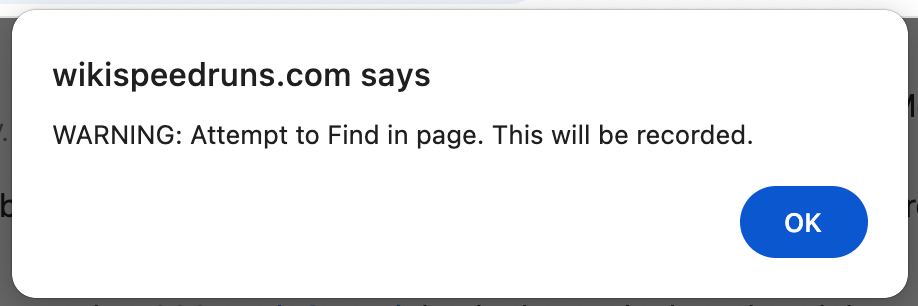

I remember playing a DIY version of this with friends, when we enforced the rules with an honor system. At some point, however, somebody created an actual app for this concept, complete with features like a daily prompt, a built-in timer, online multiplayer lobbies, and maybe most helpful (or vexing, depending on your perspective), the inability to pull up on-page search with Control+F. In fact, if you try, you’ll be told off with an ominous message.

The most impressive scores go to those with the greatest sense of the connections between domains of knowledge—those who can best intuit which kinds of cross-references they’ll be able to find on any given article.

I have to imagine that some particularly competitive players end up editing certain Wikipedia entries themselves, adding more links to make the game easier—the tail wagging the dog. (Or maybe the better idiom is “the medium is the message,” since Wikipedia’s editable, hyperlinked structure enables and encourages its unintended use as a game space instead of a knowledge source. It’s like how some people will perceive the built environment as a parkour playground.) If this gamification encourages more people to flesh out Wikipedia, is that really a bad thing?

Wikipedia Speedruns highlight the advantages of a robust bottom-up information architecture—one where the connections between pages emerge organically through countless user-generated links, instead of a centrally planned, top-down hierarchy. Most concepts are fewer steps apart than one might initially guess!

Codenames

Codenames is a word-association game where players try to identify their team’s secret words on a grid using one-word clues and numbers. The first team to guess all of their words correctly wins.

One player from each team is designated as the “Spymaster,” who can see which words correspond to which team. They give clues to their team members, the “Field Operatives,” who must guess which word belongs to which team based on these clues. The Spymaster must be careful not to give clues that inadvertently lead their team to choose the “assassin,” a word that leads to an instant loss if guessed.

For example: let’s say the words on the grid include:

Apple, Mercury, Whale, Rocket, Pyramid, Egypt, Dolphin, Table, Ice, MoonAnd one team’s target words are:

Rocket, Moon, Mercury, IceThe Spymaster might say “Space, 3” as their clue. The number indicates the number of words that the Spymaster thinks relate to their clue word, “Space.” Given this clue, the Field Operatives can discuss among themselves and correctly guess “Rocket,” “Moon,” and “Mercury” as among the target words. At the next turn, the Spymaster can give a clue for “Ice.” (It’s impressive if a Spymaster can suggest three target words with one clue; oftentimes it’s easier to try a clue that points to only one or two target words.) Meanwhile, if the “assassin” word is “Dolphin,” then the Spymaster won’t want to give a clue like “Water, 2” because, although “Water” might lead his team to guess “Ice,” (water turns into ice) it could also lead them to guess “Dolphin” (dolphins live in water) and then they would all lose the game.

To be good at Codenames requires one to creatively leverage the semantic relationships between words—to envision how words are related in meaning, category, and association. Information architects use this skill to come up with taxonomies, tagging systems, and content hierarchies. Good information architecture reduces ambiguity through smart labeling and contextual clues, in the same way that a smart Codenames clue will be precise without overreaching.

The players of this game also need to regard the mental models of their team members to avoid giving or interpreting clues in a way that would not be intuitive to the other members of their team. This is another skill that information architects use to avoid, for example, creating a confusing or poorly structured website for users.

Labeling is the other obvious parallel to information architecture work. Clues in Codenames function as labels that need to categorize multiple target words effectively, which is done by keeping those labels intuitive and descriptive. Poor labels confuse users, but in Codenames they will cost you the game.

Codenames started as a board game, but I’ve played it (in my information architecture team at work, no less) in a free online version. The rules can take a little while to grasp but once the players understand, the game feels analogous to the work information architects do in structuring meaning.

Semantris

Semantris, a name seemingly derived from a portmanteau of “semantics” and Tetris, is a word association game created by Google and powered by machine learning.

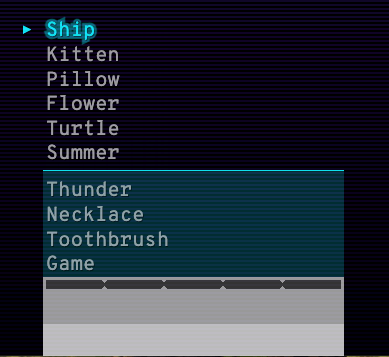

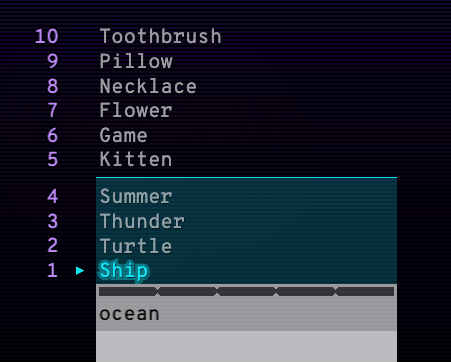

You are given a list of words, and you need to sort them by entering a word of your own. The list sorts itself so that the words most related to yours move to the bottom of the list. Your goal is to make the highlighted words appear below a certain threshold—in other words, to quickly come up with a word that somehow closely relates to the highlighted word.

In the photo above, I used the word “Ocean” to relate to “Ship” but there are a number of other words that probably would have worked just as well, such as “Boat” or “Vessel” (synonyms), or even words like “Car” or “Airplane” (which relate because they are also modes of transportation). This is a game that could not exist without modern-day machine learning tools.

Semantris starts easy but quickly gets hectic, at least when you’re playing on “Arcade Mode.” There’s also a “Blocks” mode which acts more as a puzzle game where you can take your time between words, but I haven’t bothered with it much.

From an information architecture perspective, Semantris feels like a stream-of-consciousness taxonomy exercise. You’re racing against an aggressive clock to generate words that connect across countless dimensions. I’m surprised this game isn’t more well known because I think it’s a lot of fun.

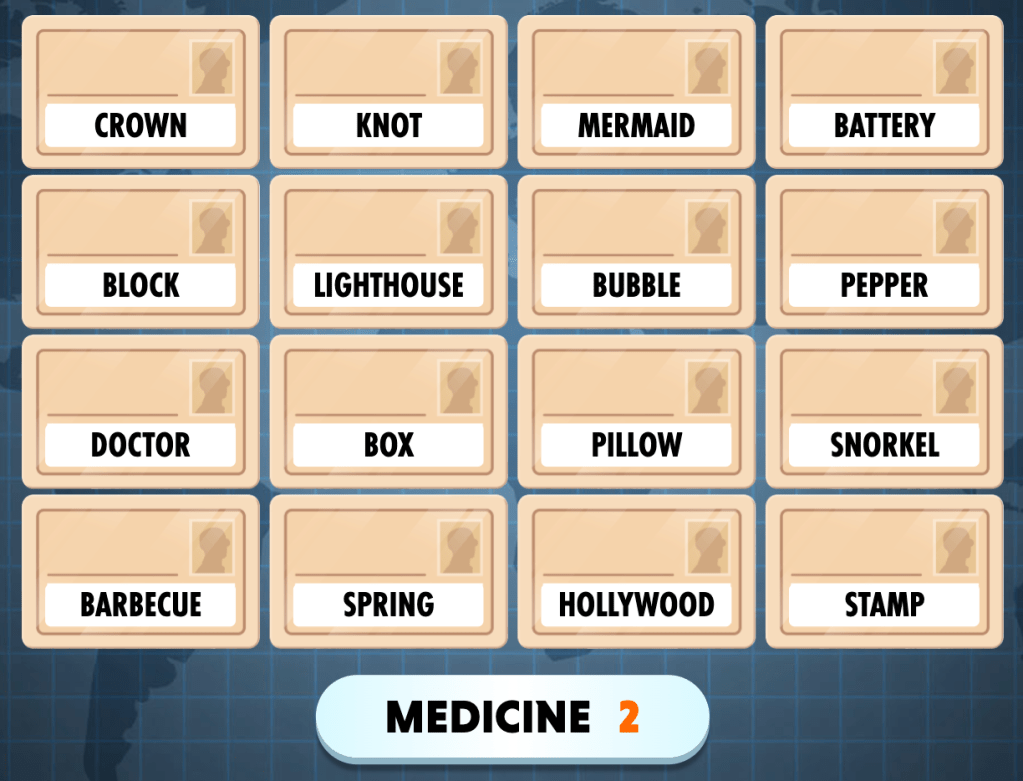

Connections

Finally we come to perhaps the most popular of the games on this list—the New York Times’ daily Connections puzzle.

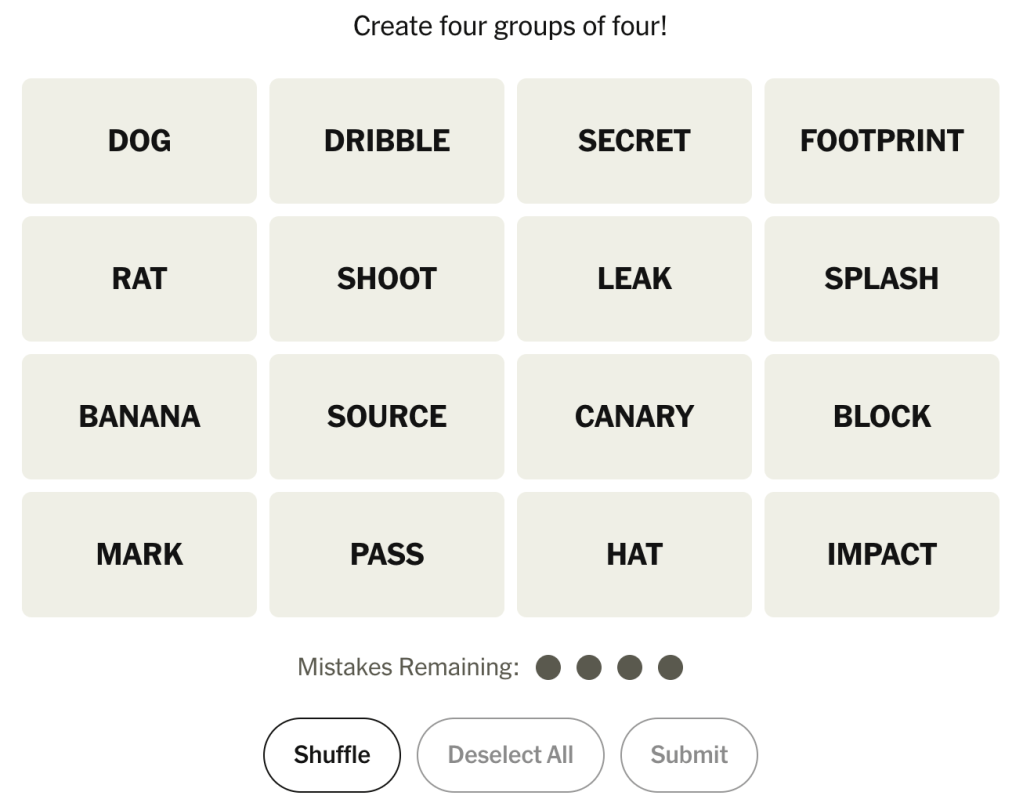

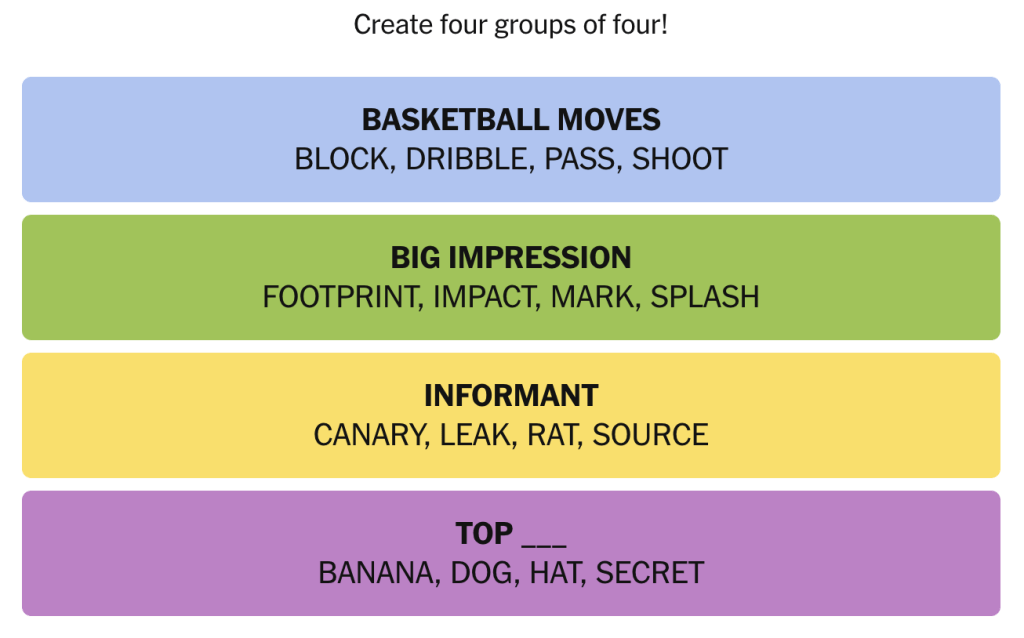

In Connections, you are presented with sixteen keywords to sort into four categories of four. The editor of the puzzle picks the categories, and while some of them can be simple and obvious, others are a real challenge. You are allowed up to four misses before you lose the game.

Connections is like a gamified card sort. You have to get inside the head of the editor of the puzzle to understand their mental model when they designed the puzzle. Even if you can justify your category to yourself (“All these words contain the letter ‘e’!”) the correct categories are more likely something cleverer. (Some people have complained that the game can be hard for international audiences because some of the categories are US-centric.)

I play this every day and share my results in a Discord server with friends, and there has been more than one occasion where I have called BS at one of the solution categories! There are some days where the editor definitely throws in red herrings.

There are also fan-made tools online that let you create and share your own Connections puzzles. The fun in making them often lies in being a charmingly obtuse information architect, not choosing categories that are too obvious but crafting some that could be misleading. In that sense, Connections might be less effective than some of the other games on this list at sharpening your semantic association skills. But it’s better at letting you be a sneaky smartass, which is fun, too.

Conclusion

I can’t guarantee that playing any of these games will make you a more employable information architect, but I do think they will boost your skills better than, say, Halo or Fortnite. Give them a try and let me know if you can think of any other neat games where you win by making clever semantic connections!